The british west african conquests

At the beginning of the 19th century, Britain's main interest was in trade with India, which it had come to dominate by the end of the 18th century. The British interest in Africa was incidental to this--ships bound to and from India had to pass along the African coast where they obtained supplies and occasionally became shipwrecked. Only a few spots in West Africa, like the Gold Coast and the Slave Coast (modern Nigeria), offered enough profit to make them attractive in their own right, so that by the end of "the Scamble" the British occupied only the Gambia, Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast and Nigeria. Naturally, the British also acquired extensive holdings elsewhere in Africa, notably in Egypt, Kenya and South Africa, but in West

At the beginning of the 19th century, Britain's main interest was in trade with India, which it had come to dominate by the end of the 18th century. The British interest in Africa was incidental to this--ships bound to and from India had to pass along the African coast where they obtained supplies and occasionally became shipwrecked. Only a few spots in West Africa, like the Gold Coast and the Slave Coast (modern Nigeria), offered enough profit to make them attractive in their own right, so that by the end of "the Scamble" the British occupied only the Gambia, Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast and Nigeria. Naturally, the British also acquired extensive holdings elsewhere in Africa, notably in Egypt, Kenya and South Africa, but in West Africa, most of the territory went to the French.

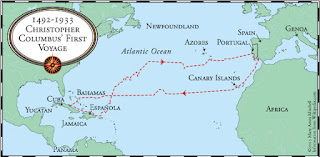

Locations mentioned in this reading

Most British attitudes about Africa were shaped by their experience with the slave trade. The British first became involved in the trade in the 16th century and became major playersby the 18th century. Most merchant seaman had seen slaves at some time in their career and in the late 18th century the abolition movement began to introduce Africans and their land to a wider audience in Great Britain. The anti-slavery movement scored its first major victory during the Napoleonic Wars when the British government outlawed the transport of slaves in ships as part of its economic war against France's "Continental System." Afterwards, British ships were stationed at Freetown in Sierra Leone with the mission to suppress the slave trade by seizing slave ships.

In the late eighteenth century, industrialization began to stimulate interest in Africa among another portion of English society--wealthy gentlemen who sought opportunities for commerce. A group that included Joseph Banks, a member of Captain Cook's 1868 expedition to the Pacific, formed the "Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa" (later known simply as the Africa Association) in 1788. Their main activity was to provide funding for expeditions to Africa and public lectures to present the results. Their earliest projects included expeditions by Simon Lucas and John Ledyard, which never gotunder way , an expedition by Daniel Houghton which ended with his disappearance east of the Gambia River, and an expedition by Mungo Park, who made it to the Niger River and back in 1795-1797. [Read Mungo Park's Life and Travels.]

After 1800, the British government became more directly involved with African exploration. The government sponsored Mungo Park's second expedition in 1805 and sent an expedition to the Ashanti capital at Kumasi, inland from the Gold Coast, in 1817. In 1819, the government established an AdmiraltyCout at Freetown to hear cases involving slave ships seized along the West African coast.

Despite the anti-slavery fervor stirred up by the West Africa Squadron and the publication of T. E. Bowditch's influential book, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee (London, 1819), British interest in Africa declined from 1815 to the 1840s. The main activity was carried out by merchants at trading posts along the Gold Coast and on James Island at the mouth of the Gambia River.

British public interest increased again in the 1840s after an attempt to colonize the Lower Niger Valley for the purpose of producing palm oil in 1841-1842. Although many of the white colonists succumbed to disease, the expedition generated news accounts and stimulated an outpouring of new publications containingtraveller's tales. A decade later, William Balfour Baikie achieved a major breakthrough when every member of his expedition returned alive after four months on the Lower Niger River in 1852, thanks to twice-daily doses of quinine taken to prevent malaria.

Most British attitudes about Africa were shaped by their experience with the slave trade. The British first became involved in the trade in the 16th century and became major players

In the late eighteenth century, industrialization began to stimulate interest in Africa among another portion of English society--wealthy gentlemen who sought opportunities for commerce. A group that included Joseph Banks, a member of Captain Cook's 1868 expedition to the Pacific, formed the "Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa" (later known simply as the Africa Association) in 1788. Their main activity was to provide funding for expeditions to Africa and public lectures to present the results. Their earliest projects included expeditions by Simon Lucas and John Ledyard, which never got

After 1800, the British government became more directly involved with African exploration. The government sponsored Mungo Park's second expedition in 1805 and sent an expedition to the Ashanti capital at Kumasi, inland from the Gold Coast, in 1817. In 1819, the government established an Admiralty

Despite the anti-slavery fervor stirred up by the West Africa Squadron and the publication of T. E. Bowditch's influential book, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee (London, 1819), British interest in Africa declined from 1815 to the 1840s. The main activity was carried out by merchants at trading posts along the Gold Coast and on James Island at the mouth of the Gambia River.

British public interest increased again in the 1840s after an attempt to colonize the Lower Niger Valley for the purpose of producing palm oil in 1841-1842. Although many of the white colonists succumbed to disease, the expedition generated news accounts and stimulated an outpouring of new publications containing

Tapping an oil palm in Sierra Leone

Source: T. J.Alldridge , A Transformed Colony

THE GAMBIA

To sailors heading south along Africa's Atlantic Coast, the Gambia River was a delight. Beginning as a wide, deep estuary, it is navigable for about 120 miles by ocean-going sailing ships, another 80 miles by smaller craft to the Barokunda Falls, and an additional 140 miles to the edge of the Futa Jalon mountains by canoe. Beginning in the 15th century, ships from all parts of Europe dropped anchor in the estuary to refit and find supplies before continuing their voyages. During the era of the slave trade, Europeans and Africans used the Gambia as a route to the interior. In the era of legitimate trade, the Gambia provided safe anchorages for merchant ships seeking peanuts, vegetable gum, animal hides and other local products.

In 1889, France agreed to cede a strip of land along each side of the Gambia to the British, and after negotiations that lasted until 1904, finally agreed to a ten-mile wide strip, roughly the area that could be reached by naval artillery of the era. The result was an odd-shaped British colony that was surrounded on three sides by the French colony of Senegal.

Source: T. J.

THE GAMBIA

In 1889, France agreed to cede a strip of land along each side of the Gambia to the British, and after negotiations that lasted until 1904, finally agreed to a ten-mile wide strip, roughly the area that could be reached by naval artillery of the era. The result was an odd-shaped British colony that was surrounded on three sides by the French colony of Senegal.

SIERRA LEONE

Sierra Leone comprises the land between coast and the south side of the Futa Jalon mountains. Although it has no large rivers, there are many smaller ones and the area is largely covered with tropical forest. In 1787, British abolitionists began to resettle freed slaves at an agricultural colony called "Freetown" located beside a bay near the "Lion Rock." After a difficult start, they received a government charter for the Sierra Leone Company in 1791. In 1808, the government began to administer the colony directly.

The colony became moderately successful thanks to the efforts of American and British Methodist missionaries, immigrationby loyalist blacks from the thirteen American colonies and the foundation of Fourah Bay College by the Church Missionary Society. The colony also received annual subsidies from the British Parliament, and by 1833 Freetown's population included two hundred whites and more than 30,000 British Africans (plus an unknwn number of indigenous "up-country" Africans--the original inhabitants of the area). The governor of Sierra Leone received authority over British possessions on the African coast from the Gambia to the Gold Coast. The borders of Sierra Leone were finally delineated in 1895, the year that the British began to build a railroad into the interior.

Sierra Leone comprises the land between coast and the south side of the Futa Jalon mountains. Although it has no large rivers, there are many smaller ones and the area is largely covered with tropical forest. In 1787, British abolitionists began to resettle freed slaves at an agricultural colony called "Freetown" located beside a bay near the "Lion Rock." After a difficult start, they received a government charter for the Sierra Leone Company in 1791. In 1808, the government began to administer the colony directly.

The colony became moderately successful thanks to the efforts of American and British Methodist missionaries, immigration

THE LOWER NIGER RIVER

In 1882, the year that the British occupied Egypt, a British trading company lobbied for government protection of their monopoly on palm oil exports from the Lower Niger River. The principal figure in the company was George Taubman Goldie, a Royal Engineer who entered the Niger River trade as a result of some company shares that he received from his uncle. In 1879, he organized a number of small trading firms into the United African Company (UAC), and in 1882 they changed their name to the National African Company (NAC).Two French firms, the Compagnie Français

Following the Congress of Berlin, the British government announced a formal protectorate over the Lower Niger River Valley in June 1885. To administer their protectorate, they granted Goldie's company a royal charter as the "Royal Niger Company." They left the issue of the border between the Lower Niger Valley, which they claimed, and the Middle Niger Valley, which the British recognized as a French sphere of influence, until later. The border was eventually settled by the Anglo-French Agreement of 14 June 1898.

GOLD COAST AND ASHANTI

The Ashanti Federation, which controlled gold production in the interior, survived

Images like these excited the British public during the Second Anglo-Ashanti War

Source: London Illustrated News (March 21, 1874)

The real African power in the region was held by the Ashanti Federation, with its capital at Kumasi in the center of the gold- producing region. The British fought against the Ashanti four times in the 19th century and suppressed a final uprising in 1900 before claiming the region as a colony. The first Anglo-Ashanti War began in 1823 after the Ashanti defeated a small British force under Sir Charles McCarthy and converted his skull into a drinking cup. It ended with a standoff after the British beat an Ashanti army near the coast in 1826. After two generations of relative peace, more violence occurred in 1863 when the Ashanti invaded the British "protectorate" along the coast in retaliation for the refusal of Fanti leaders to return a fugitive slave. The result was anotherstand-off , but the British

In 1873, the Second Ashanti War began after the British took possession of the remaining Dutch trading posts along the coast, giving British firms a regional monopoly on the trade between Africans andEurope . The Ashanti had long viewed the Dutch as allies, so they invaded the British protectorate along the coast. A British army led by General Wolseley waged a successful campaign against the Ashanti that led to a brief occupation of Kumasi and a "treaty of protection" signed by the Ashantehene (leader) of Ashanti, ending the war in July 1874. This war was covered by a number of news correspondents (including H. M. Stanley) and the "victory" excited the imagination of the European public.

Source: London Illustrated News (March 21, 1874)

The real African power in the region was held by the Ashanti Federation, with its capital at Kumasi in the center of the gold- producing region. The British fought against the Ashanti four times in the 19th century and suppressed a final uprising in 1900 before claiming the region as a colony. The first Anglo-Ashanti War began in 1823 after the Ashanti defeated a small British force under Sir Charles McCarthy and converted his skull into a drinking cup. It ended with a standoff after the British beat an Ashanti army near the coast in 1826. After two generations of relative peace, more violence occurred in 1863 when the Ashanti invaded the British "protectorate" along the coast in retaliation for the refusal of Fanti leaders to return a fugitive slave. The result was another

In 1873, the Second Ashanti War began after the British took possession of the remaining Dutch trading posts along the coast, giving British firms a regional monopoly on the trade between Africans and

In 1894, the Third Anglo-Ashanti War began following British press reports that a new Ashantehene named Prempeh committed acts of cruelty and barbarism. Strategically, the British used the war to insure their control over the gold fields before the French, who were advancing on all sides, could claim them. In 1896, the British government formally annexed the territories of the Ashanti and the Fanti. In 1900, a final uprising took place when the British governor of Gold Coast (Hodgson) unilaterally attempted to depose the Ashantehene by seizing the symbol of his authority, the Golden Stool. The British were victorious and reoccupied Kumasi permanently.

On September 26, 1901 the British created the Crown Colony of Gold Coast. The change in the Gold Coast's status from "protectorate" to "crown colony" meant that relations with the inhabitants of the region were handled by the Colonial Office, rather than the Foreign Office. That implied that the British no longer recognized the Ashanti or the Fanti as having independent governments.

Comments

Post a Comment