ashanti: a country like no other

foreword

|

| warrior in ashanti |

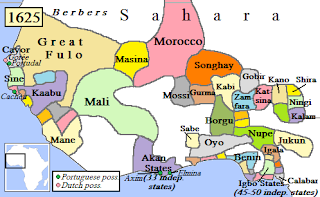

the Brong-Ahafo, Central region, Eastern region,Greater Accra region, and Western region, of present-day Ghana. Ashanti people used military power due to effective strategy and early firearm adoption to create an empire that stretched from central Ghana to the present-day Ivory Coast. Due to the empire's military prowess, wealth, architecture, sophisticated hierarchy and culture, the Ashanti empire was extensively studied and has more historical studies by European, mainly British, authors than almost any other indigenous culture of Sub-Saharan Africa.

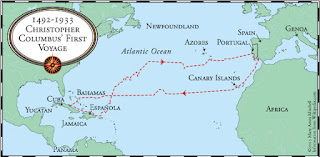

the ashanti empire established during the late 17thn centurie by the late king osei tutu (1695 - 1717), he unified the territories with a golden stool of ahanti as a prime unification symbol, he manipulated through major ashanti territorial expansion, with a formidable army and great asante wealth at his disposal; he oversaw expansion of territories up to the gulf of guinea and the Atlantic Ocean coastal trade with Europeans, notably the Dutch.

historical background

Ashanti political organization was originally centered on clans headed by a paramount chief or Amanhene. One particular clan, the Oyoko, settled in the Ashanti's sub-tropical forest region, establishing a center at Kumasi.[8] The Ashanti became tributaries of another Akan state, Denkyira but in the mid-17th century the Oyoko under Chief Oti Akenten started consolidating the Ashanti clans into a loose confederation against the Denkyira.[9]

The introduction of the Golden Stool (Sika ɗwa)

was a means of centralization under Osei Tutu. According to legend, a

meeting of all the clan heads of each of the Ashanti settlements was

called just prior to independence from Denkyira.

In this meeting the Golden Stool was commanded down from the heavens by

Okomfo Anokye, priest or sage advisor to Asantehene Osei Tutu I and

floated down from the heavens into the lap of Osei Tutu I. Okomfo Anokye

declared the stool to be the symbol of the new Asante Union (the Ashanti Kingdom),

and allegiance was sworn to the stool and to Osei Tutu as the

Asantehene. The newly founded Ashanti union went to war with and

defeated Denkyira.The stool remains sacred to the Ashanti as it is believed to contain the Sunsum — spirit or soul of the Ashanti people.

The introduction of the Golden Stool (Sika ɗwa)

was a means of centralization under Osei Tutu. According to legend, a

meeting of all the clan heads of each of the Ashanti settlements was

called just prior to independence from Denkyira.

In this meeting the Golden Stool was commanded down from the heavens by

Okomfo Anokye, priest or sage advisor to Asantehene Osei Tutu I and

floated down from the heavens into the lap of Osei Tutu I. Okomfo Anokye

declared the stool to be the symbol of the new Asante Union (the Ashanti Kingdom),

and allegiance was sworn to the stool and to Osei Tutu as the

Asantehene. The newly founded Ashanti union went to war with and

defeated Denkyira.The stool remains sacred to the Ashanti as it is believed to contain the Sunsum — spirit or soul of the Ashanti people.In the 1670s the head of the Oyoko clan, Osei Kofi Tutu I, began another rapid consolidation of Akan peoples via diplomacy and warfare. King Osei Kofu Tutu I and his chief advisor, Okomfo Kwame Frimpong Anokye led a coalition of influential Ashanti city-states against their mutual oppressor, the Denkyira who held the Ashanti Kingdom in its thrall. The Ashanti Kingdom utterly defeated them at the Battle of Feyiase, proclaiming its independence in 1701. Subsequently, through hard line force of arms and savoir-faire diplomacy, the duo induced the leaders of the other Ashanti city-states to declare allegiance and adherence to Kumasi, the Ashanti capital. From the beginning, King Osei Tutu and priest Anokye followed an expansionist and an imperialistic provincial foreign policy. According to folklore, Okomfo Anokye is believed to have visited Agona-Akrofonso.

social structure

Standing among families was largely political. The royal family typically tops the hierarchy, followed by the families of the chiefs of territorial divisions. In each chiefdom, a particular female line provides the chief. A committee from among several men eligible for the post elects that chief.

The Ashanti held puberty rites only

for females. Fathers instruct their sons without public observance. The

privacy of boys was respected in the Ashanti kingdom. As menstruation approaches,

a girl goes to her mother's house. When the girl's menstruation is

disclosed, the mother announces the good news in the village beating an

iron hoe with a stone. Old women come out and sing Bara (menstrual) songs.

Menstruating

women suffered numerous restrictions. The Ashanti viewed them as

ritually unclean. They did not cook for men, nor did they eat any food

cooked for a man. If a menstruating woman entered the ancestral stool house,

she was arrested, and the punishment was typically death. If this

punishment is not exacted, the Ashanti believe, the ghost of the ancestors would strangle the chief.

Menstruating women lived in special houses during their periods as they

were forbidden to cross the threshold of men's houses. They swore no oaths and no oaths were sworn for or against them. They did not participate in any of the ceremonial observances and did not visit any sacred places.

ceremonies in the ashante is quite elaborate and The greatest and most frequent ceremonies of the Ashanti recalled the spirits of departed rulers with an offering of food and drink, asking their favor for the common good, called the Adae. The day before the Adae, Akan drums broadcast the approaching ceremonies. The stool treasurer gathers sheep and liquor that will be offered. The chief priest officiates the

Adae in the stool house where the ancestors came. The priest offers each food and a beverage. The public ceremony occurs outdoors, where all the people joined the dancing. Minstrels chant ritual phrases; the talking drums extol the chief and the ancestors in traditional phrases. The Odwera, the other large ceremony, occurs in September and typically lasted for a week or two. It is a time of cleansing of sin from society the defilement, and for the purification of shrines of ancestors and gods. After the sacrifice and feast of a black hen; of which both the living and the dead share, a new year begins in which all were clean, strong, and healthy.

European contact with the Asante on the Gulf of Guinea coast region of Africa began in the 19th century. This led to trade in gold, ivory, slaves, and other goods with the Portuguese, which gave rise to kingdoms such as the Ashanti. On May 15, 1817 the Englishman Thomas Bowdich entered Kumasi. He remained there for several months, was impressed, and on his return to England wrote a book, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee. His praise of the kingdom was disbelieved as it contradicted prevailing prejudices. Joseph Dupuis,

the first British consul in Kumasi, arrived on March 23, 1820. Both

Bowdich and Dupuis secured a treaty with the Asantehene. But, the

governor, Hope Smith, did not meet Ashanti expectations.

European contact with the Asante on the Gulf of Guinea coast region of Africa began in the 19th century. This led to trade in gold, ivory, slaves, and other goods with the Portuguese, which gave rise to kingdoms such as the Ashanti. On May 15, 1817 the Englishman Thomas Bowdich entered Kumasi. He remained there for several months, was impressed, and on his return to England wrote a book, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee. His praise of the kingdom was disbelieved as it contradicted prevailing prejudices. Joseph Dupuis,

the first British consul in Kumasi, arrived on March 23, 1820. Both

Bowdich and Dupuis secured a treaty with the Asantehene. But, the

governor, Hope Smith, did not meet Ashanti expectations.

All Ashanti attempts at negotiations were disregarded. Wolseley led 2,500 British troops and several thousand West Indian and African troops to Kumasi. The capital was briefly occupied. The British were impressed by the size of the palace and the scope of its contents, including "rows of books in many languages." The Ashanti had abandoned the capital after a bloody war. The British burned it.

The Ashanti Kingdom wanting to keep French and European colonial forces out of the Ashanti Kingdom territory (and its gold), the British were anxious to conquer the Ashanti Kingdom once and for all. Despite being in talks with the kingdom about making it a British protectorate, Britain began the Fourth Anglo-Ashanti War in 1895 on the pretext of failure to pay the fines levied on the Asante monarch after the 1874 war. The British were victorious and the Ashanti Kingdom was forced to sign a treaty.

As King, the Asantehene held immense power in Ashanti, but did not enjoy absolute royal rule. He was obliged to share considerable legislative and executive powers with Asante's sophisticated bureaucracy. But the Asantehene was the only person in Ashanti permitted to invoke the death sentence

in cases of crime. During wartime, the King acted as Supreme Commander

of the army, although during the 19th century, the fighting was

increasingly handled by the Ministry of War in Kumasi. Each member of

the confederacy was also obliged to send annual tribute to Kumasi.

The Ashantihene (King of all Ashanti) reigns over all and chief of the division of Kumasi, the nation’s capital, and the Ashanti Kingdom. He is elected in the same manner as all other chiefs. In this hierarchical structure, every chief swears fealty to the one above him—from village and subdivision, to division to the chief of Kumasi, and the Ashantihene swears fealty to the State.

The elders circumscribe the power of the Ashantihene, and the chiefs of other divisions considerably check the power of the King. This in practical effect creates a system of checks and balances. As the symbol of the nation, the Ashantihene receives significant deference ritually, for the context is religious in that he is a symbol of the people in the flesh: the living, dead or yet to be born. When the king commits an act not approved of by the counsel of elders or the people, he could possibly be impeached, and demoted to a commoner.

The existence of aristocratic organizations and the council of elders is evidence of an oligarchic tendency in Ashanti political life. Though older men tend to monopolize political power, Ashanti instituted an organization of young men, the nmerante, that tend to democratize and liberalize the political process. The council of elders undertake actions only after consulting a representative of the nmerante. Their views must be taken seriously and added into the conversation.

Below the Asantahene, local power was invested in the obirempon of each locale. The obirempon

(literally "big man") was personally selected by the Asantahene and was

generally of loyal, noble lineage, frequently related to the

Asantahene. Obirempons had a fair amount of legislative power in

their regions, more than the local nobles of Dahomey but less than the

regional governors of the Oyo Empire. In addition to handling the

region's administrative and economic matters, the obirempon also acted as the Supreme Judge of the region, presiding over court cases.

sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashanti_Empire

http://www.blackpast.org/gah/ashanti-empire-asante-kingdom-18th-late-19th-century

ceremonies in the ashante is quite elaborate and The greatest and most frequent ceremonies of the Ashanti recalled the spirits of departed rulers with an offering of food and drink, asking their favor for the common good, called the Adae. The day before the Adae, Akan drums broadcast the approaching ceremonies. The stool treasurer gathers sheep and liquor that will be offered. The chief priest officiates the

Adae in the stool house where the ancestors came. The priest offers each food and a beverage. The public ceremony occurs outdoors, where all the people joined the dancing. Minstrels chant ritual phrases; the talking drums extol the chief and the ancestors in traditional phrases. The Odwera, the other large ceremony, occurs in September and typically lasted for a week or two. It is a time of cleansing of sin from society the defilement, and for the purification of shrines of ancestors and gods. After the sacrifice and feast of a black hen; of which both the living and the dead share, a new year begins in which all were clean, strong, and healthy.

European conquests and Anglo-asante wars

first European contacts

European contact with the Asante on the Gulf of Guinea coast region of Africa began in the 19th century. This led to trade in gold, ivory, slaves, and other goods with the Portuguese, which gave rise to kingdoms such as the Ashanti. On May 15, 1817 the Englishman Thomas Bowdich entered Kumasi. He remained there for several months, was impressed, and on his return to England wrote a book, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee. His praise of the kingdom was disbelieved as it contradicted prevailing prejudices. Joseph Dupuis,

the first British consul in Kumasi, arrived on March 23, 1820. Both

Bowdich and Dupuis secured a treaty with the Asantehene. But, the

governor, Hope Smith, did not meet Ashanti expectations.

European contact with the Asante on the Gulf of Guinea coast region of Africa began in the 19th century. This led to trade in gold, ivory, slaves, and other goods with the Portuguese, which gave rise to kingdoms such as the Ashanti. On May 15, 1817 the Englishman Thomas Bowdich entered Kumasi. He remained there for several months, was impressed, and on his return to England wrote a book, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee. His praise of the kingdom was disbelieved as it contradicted prevailing prejudices. Joseph Dupuis,

the first British consul in Kumasi, arrived on March 23, 1820. Both

Bowdich and Dupuis secured a treaty with the Asantehene. But, the

governor, Hope Smith, did not meet Ashanti expectations.first anglo-ashanti war

The first of the Anglo-Ashanti wars

occurred in 1823. In these conflicts, the Ashanti Kingdom faced off,

with varying degrees of success, against the British Empire residing on

the coast. The root of the conflict traces back to 1823 when Sir Charles MacCarthy,

resisting all overtures by the Ashanti to negotiate, led an invading

force. The Ashanti defeated this, killed MacCarthy, took his head for a

trophy and swept on to the coast. However, disease forced them back. The

Ashanti were so successful in subsequent fighting that in 1826 they

again moved on the coast. At first they fought very impressively in an

open battle against superior numbers of British allied forces, including

Denkyirans. However, the novelty of British rockets caused the Ashanti

army to withdraw. In 1831, a treaty led to 30 years of peace, with the Pra River accepted as the border.

second anglo-ashanti war

With the exception of a few Ashanti light skirmishes across the Pra

in 1853 and 1854, the peace between the Ashanti Kingdom and the British

Empire had remained unbroken for over 30 years. Then, in 1863, a large

Ashanti delegation crossed the river pursuing a fugitive, Kwesi Gyana.

There was fighting, casualties on both sides, but the governor's request

for troops from England was declined and sickness forced the withdrawal

of his West Indian troops. The war ended in 1864 as a stalemate with

both sides losing more men to sickness than any other factor.

third anglo-ashanti war

In 1869 a European missionary family was taken to Kumasi. They were hospitably welcomed and were used as an excuse for war in 1873. Also, Britain took control of Ashanti land claimed by the Dutch. The Ashanti invaded the new British protectorate. General Wolseley and his famous Wolseley ring were sent against the Ashanti. This was a modern war, replete with press coverage (including by the renowned reporter Henry Morton Stanley) and printed precise military and medical instructions to the troops, The British government refused appeals to interfere with British armaments manufacturers who were unrestrained in selling to both sides.All Ashanti attempts at negotiations were disregarded. Wolseley led 2,500 British troops and several thousand West Indian and African troops to Kumasi. The capital was briefly occupied. The British were impressed by the size of the palace and the scope of its contents, including "rows of books in many languages." The Ashanti had abandoned the capital after a bloody war. The British burned it.

fourth anglo-ashanti war

In 1895, the Ashanti turned down an unofficial offer to become a British protectorate.The Ashanti Kingdom wanting to keep French and European colonial forces out of the Ashanti Kingdom territory (and its gold), the British were anxious to conquer the Ashanti Kingdom once and for all. Despite being in talks with the kingdom about making it a British protectorate, Britain began the Fourth Anglo-Ashanti War in 1895 on the pretext of failure to pay the fines levied on the Asante monarch after the 1874 war. The British were victorious and the Ashanti Kingdom was forced to sign a treaty.

political pyramid

At the top of Ashanti's power structure sat the Asantehene, the King of Ashanti. Each Asantahene was enthroned on the sacred Golden Stool, the Sika 'dwa, an object that came to symbolise the very power of the King. Osei Kwadwo (1764–1777) began the meritocratic system of appointing central officials according to their ability, rather than their birth. |

| asantehene |

The Ashantihene (King of all Ashanti) reigns over all and chief of the division of Kumasi, the nation’s capital, and the Ashanti Kingdom. He is elected in the same manner as all other chiefs. In this hierarchical structure, every chief swears fealty to the one above him—from village and subdivision, to division to the chief of Kumasi, and the Ashantihene swears fealty to the State.

The elders circumscribe the power of the Ashantihene, and the chiefs of other divisions considerably check the power of the King. This in practical effect creates a system of checks and balances. As the symbol of the nation, the Ashantihene receives significant deference ritually, for the context is religious in that he is a symbol of the people in the flesh: the living, dead or yet to be born. When the king commits an act not approved of by the counsel of elders or the people, he could possibly be impeached, and demoted to a commoner.

The existence of aristocratic organizations and the council of elders is evidence of an oligarchic tendency in Ashanti political life. Though older men tend to monopolize political power, Ashanti instituted an organization of young men, the nmerante, that tend to democratize and liberalize the political process. The council of elders undertake actions only after consulting a representative of the nmerante. Their views must be taken seriously and added into the conversation.

| |

| the golden stool |

sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashanti_Empire

http://www.blackpast.org/gah/ashanti-empire-asante-kingdom-18th-late-19th-century

https://www.britannica.com/place/Asante-empire

Comments

Post a Comment